Saudi Arabia's Progress on Reducing Fossil Fuel Dependence

Ashby just dropped a big paper with some of his Stanford colleagues that takes a look at Saudi Arabia’s progress on its “big push” to diversify its economy from fossil fuels.

In that paper, they advocate for continuing that effort over the long term through innovative use of the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), which includes expanding its mandate to position the PIF for sustained income generation in 2030 and beyond.

The paper is too long to share with you here in its entirety — again, you can read the whole thing here — but we’ve pasted a meaty section from the middle with some great exposition about the country’s progress on reducing its fossil fuel dependence below that might be particularly interesting.

Progress on Reducing Oil Dependence: Revenue Diversification but Rising Break-Evens.

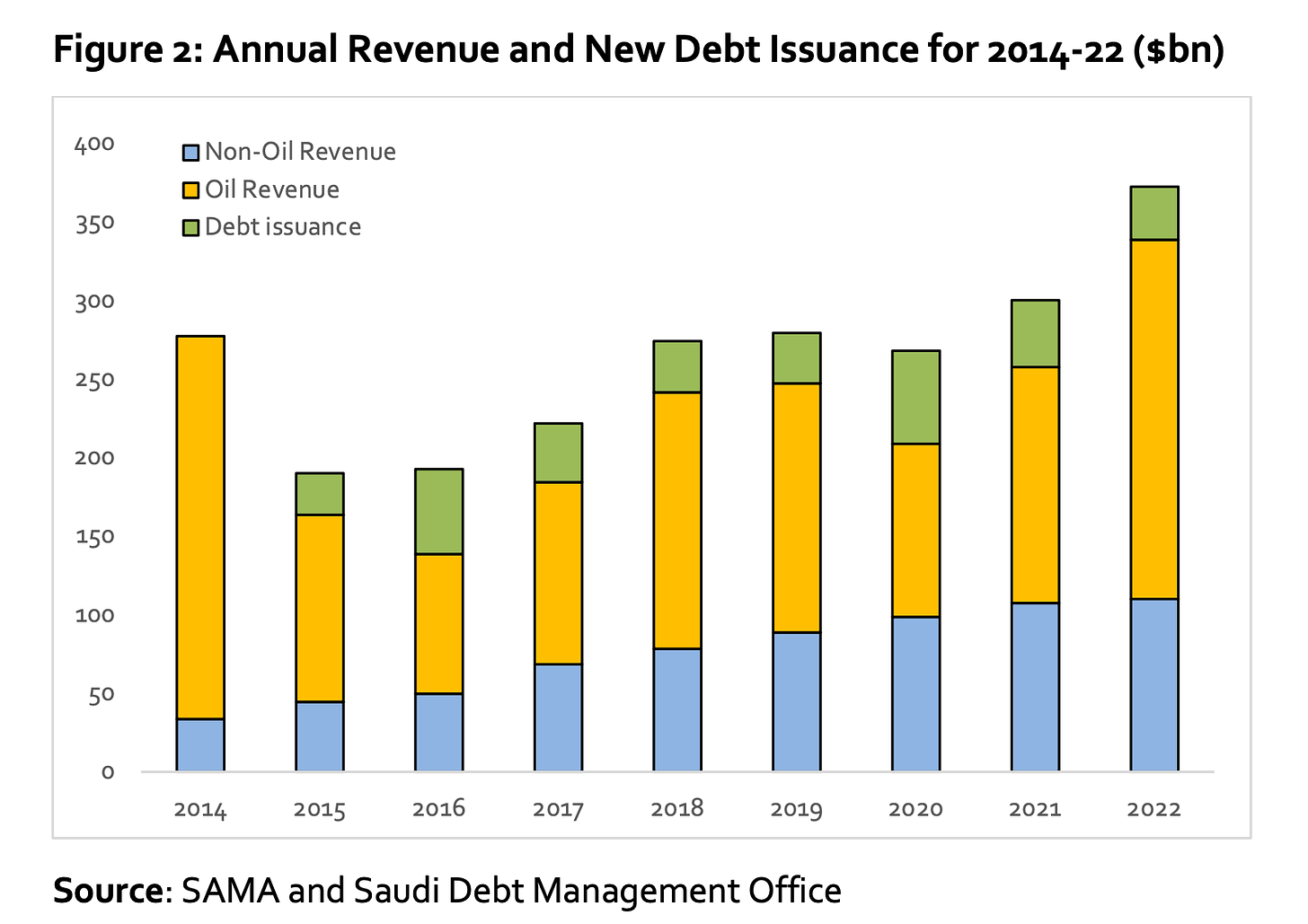

Historically, even when oil prices have fallen sharply (as in 2009 and 2014), oil’s share of total revenue in Saudi Arabia has remained above 85%, given the lack of non-oil tax revenue – and, hence, such shocks had to be met with sharp, procyclical cuts in public spending and investment. The landmark introduction of a VAT sales tax in the aftermath of the 2014 oil shock, however, initiated a structural shift that resulted in non-oil revenues growing steadily ever since. Saudi Arabia also engaged in successful debt issuances, including foreign borrowing in the aftermath of the 2014 oil price shock.

These developments mean that Saudi Arabia’s portfolio of revenue sources is now more diversified than before the 2014 shock (see Figure 2). This diversification is evident both in the total size of non-oil revenues annually and the fact that oil’s share of total revenue has remained below 70%, even during the large windfall in 2022.

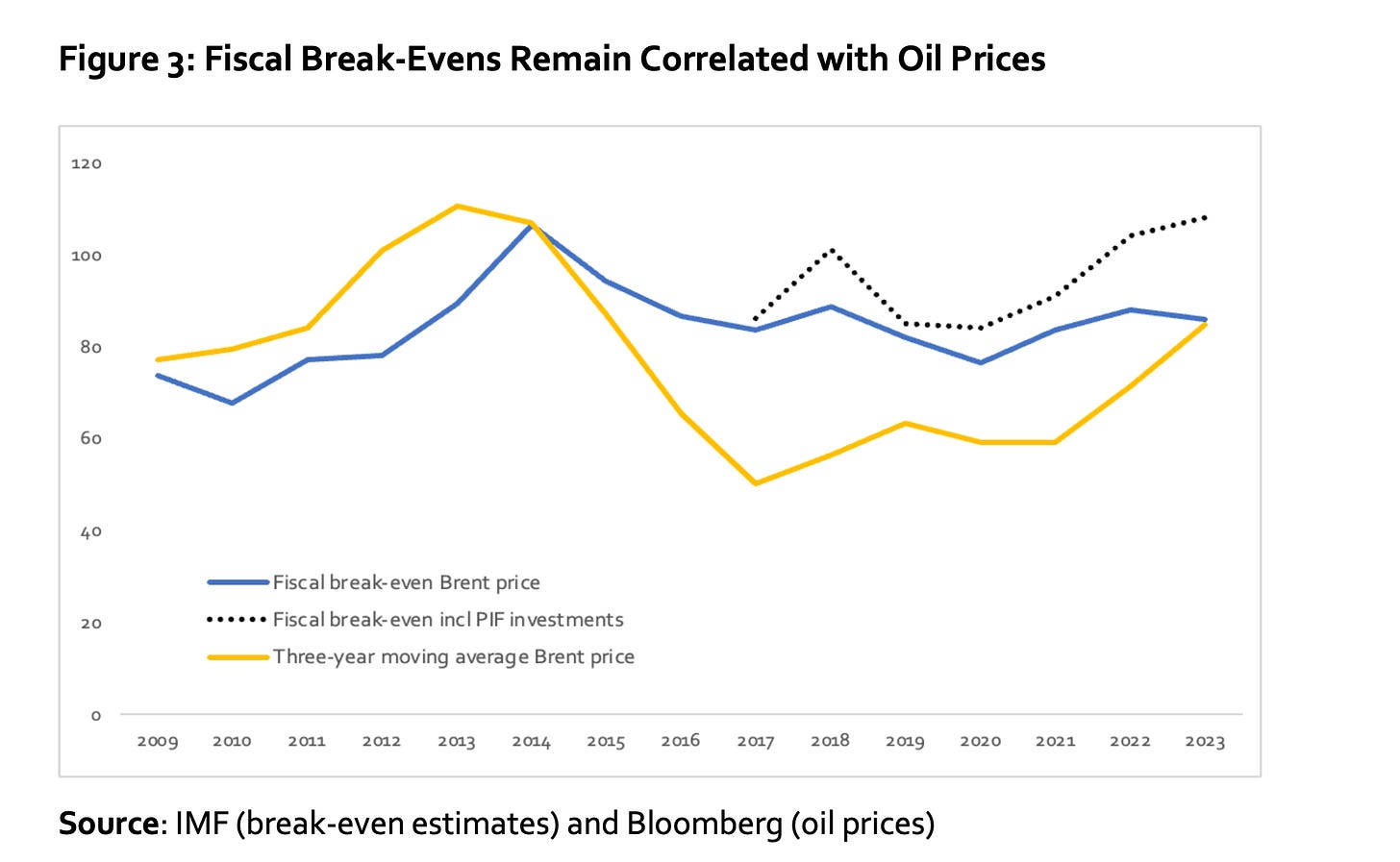

A common rule of thumb for assessing fiscal dependence on oil is to estimate the average price per barrel required to balance the budget for assumed levels of spending and oil production. Such fiscal “break-even price” estimates either assume real spending, non-oil revenues, and production volumes to be constant or following a steady growth path. In the Saudi case, production volumes are well anchored given its leadership role in OPEC, which means output typically fluctuates in a range of 9 million to 11 million barrels a day (on rare occasions widening to 8 million to 12 million barrels per day). Further, non-oil revenues can be assumed to increase steadily, while spending growth can be linked to medium-term expenditure commitments.

As shown in Figure 3, Saudi Arabia’s break-even oil price decreased after the 2014 oil-revenue shock due to the growth of non-oil revenues and a sharp reduction in spending. While most regional estimates put the Kingdom’s break-even oil price slightly above those of its peers, such as Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait, the decline in the break-even price after 2014 reflects significant progress, particularly considering the resumption of spending growth since 2019. Figure 3 should, however, be caveated: a meaningful reduction in oil dependence will break the historical tendency of break-evens to correlate with oil revenues over the cycle.

While it will take a few more years to get a better understanding of more recent fiscal dynamics in Saudi Arabia, it appears that the fiscal break-even oil price has again risen in response to increased oil revenues in 2022 and 2023. The most recent estimates by the IMF, for example, released in the fourth quarter of 2023, suggested that the most recent break-even oil price for Saudi Arabia is once again US$86 per barrel. Further, estimates of the break-even oil price that attempt to account for investment and expenditure through the PIF are higher than those focused exclusively on the budget. The increase in break-even oil prices in recent years suggests that the procyclical relationship between spending, investment and oil prices remains a concern.

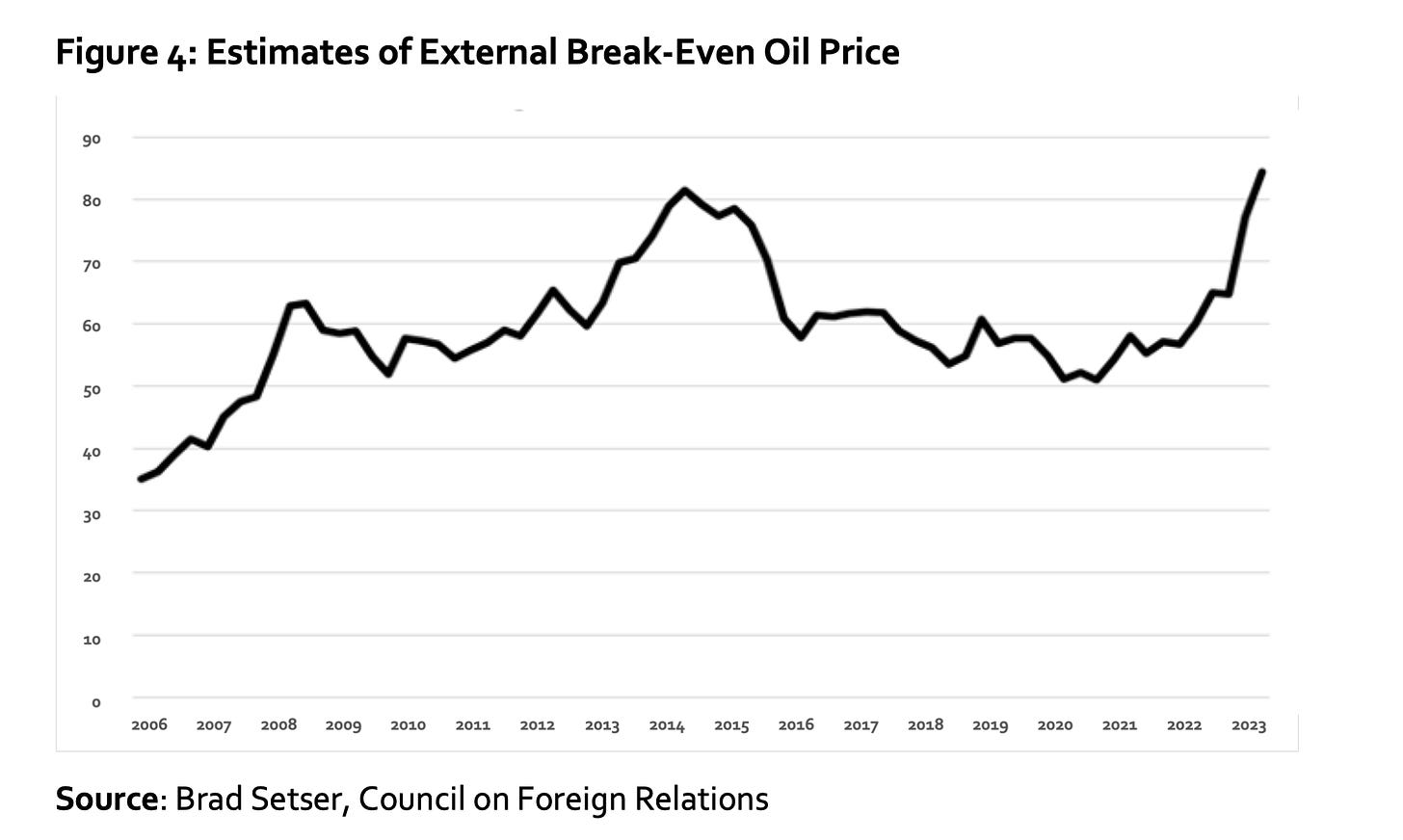

Oil dependence is also evident with respect to Saudi Arabia’s external balances. A short-hand proxy for the oil-price sensitivity of the Saudi current-account balance is to estimate an “external break-even” price for oil. This is akin to the fiscal break-even oil price, but rather than estimating the oil price required to balance the budget, the focus is rather on the oil price needed to generate sufficient export revenues to pay for imports. Figure 4 shows Brad Setser’s estimates for Saudi external break-even oil prices (see Setser and Frank, 2017 for methodology).

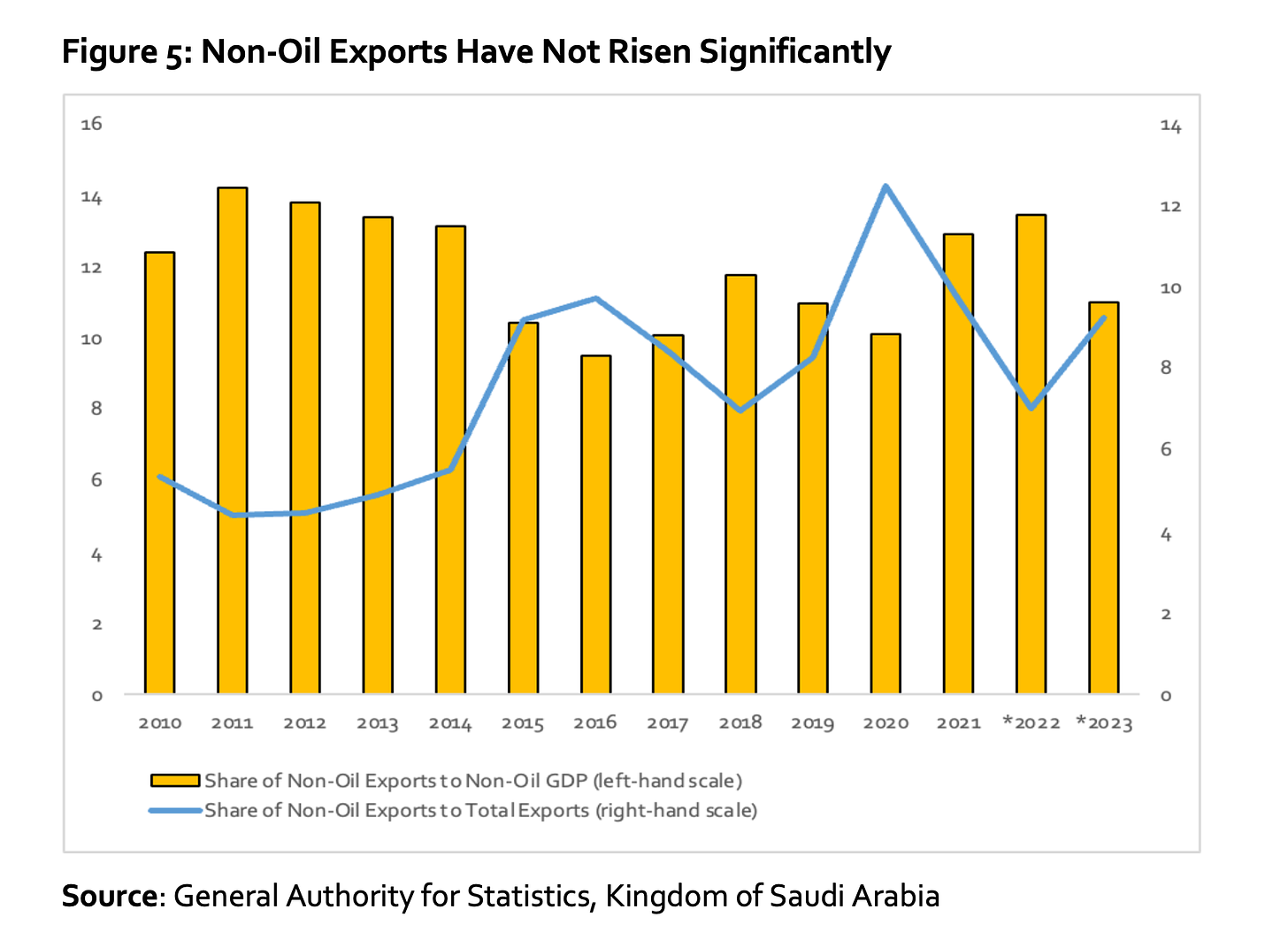

Note that the recent increase in the external break-even price for oil is in line with fiscal break-evens. Recent IMF estimates of Saudi Arabia’s external break-even oil price also show an increase from around US$50 per barrel in 2020 to over US$90 per barrel for 2024. Moreover, as shown in Figure 5, relative to both total exports and the total non-oil GDP, non-oil exports have remained relatively flat since 2010. These data indicate that Saudi Arabia remains dependent on oil revenues for external financing.

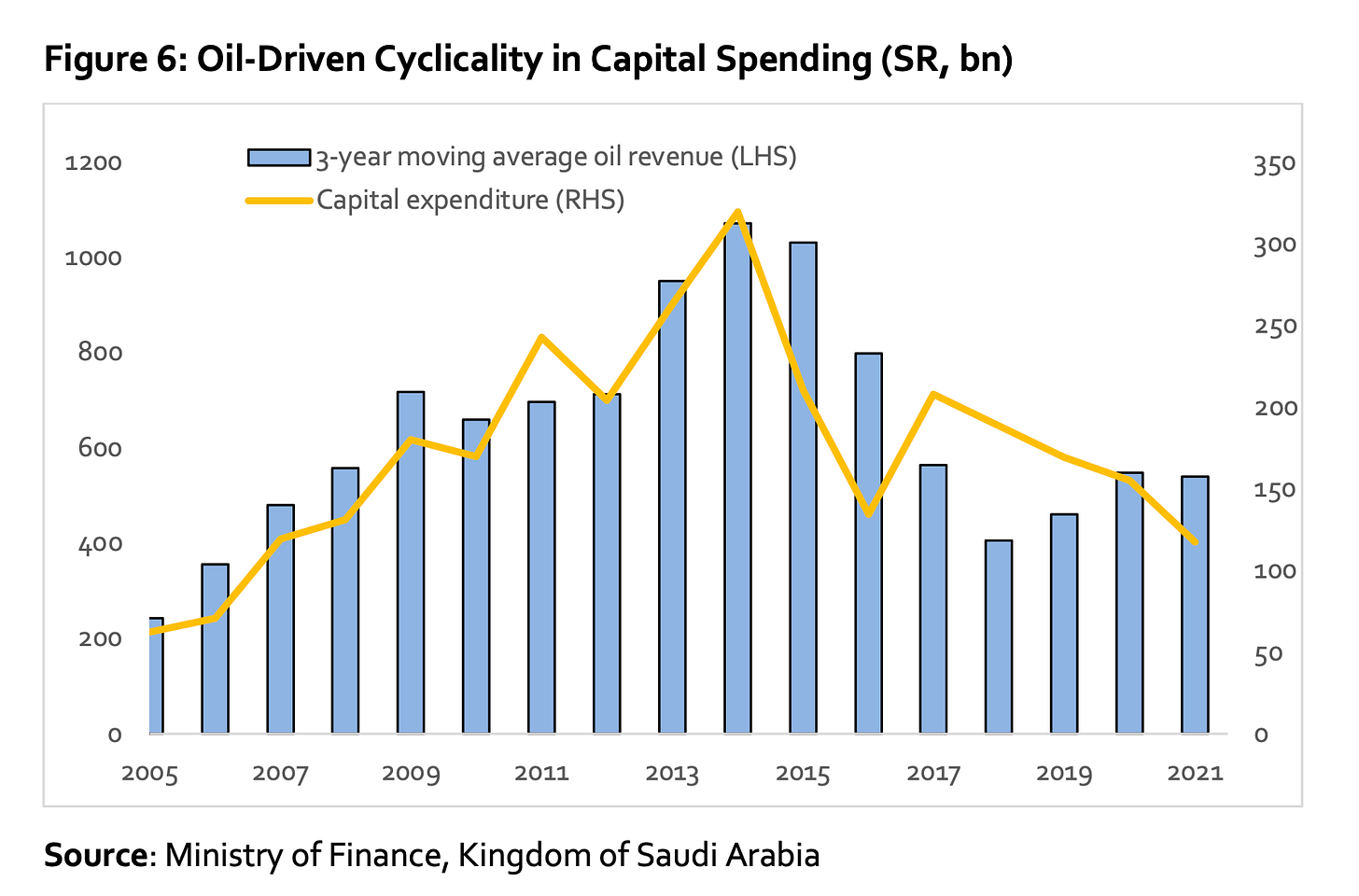

Finally, oil dependence also manifests through cyclical correlation between oil and various economic indicators. Procyclicality is evident in the historical correlation between capital expenditure and oil revenues, shown in Figure 6. This correlation suggests that the burden of fiscal adjustment has historically fallen on the capital-spending component of the budget. Given the central role of the PIF in capital projects and infrastructure investments, a key objective is ensuring these can be sustained in the event of lower oil revenues, breaking the historic tendency to freeze capital projects when oil revenues decline.

A stop-start pattern in public investment is problematic from a diversification perspective and presents a potential challenge to the Vision 2030 agenda, should oil revenues decline. Commodity-dependent, high-cost economies need patient capital in which investment is sustained beyond the medium term. The relative absence of obvious “low-hanging fruit” in the effort for diversification of the Saudi economy requires a Long Push, rather than a Big Push – thereby putting a premium on institutions and policies that can promote countercyclical resilience and sustainability.

Overall, the 2014 oil-revenue shock and its aftermath initiated important fiscal reforms, notably the growth of non-oil revenues and successful debt issuances. That said, the recent increase in fiscal and external break-even price of oil, in correlation with higher oil prices and revenues, suggests that the procyclical tendencies remain. Macroeconomic stability and fiscal resilience, therefore, persist as notable risks in the event of sharp or protracted decline in oil revenues. In the remainder of this paper, we consider policies that will enhance sustainability, stability and resilience – which are critical to the transition from the Big Push to the Long Push.

IV. Increasing Resilience

The Role of Foreign Assets and Investment Income

While 2024 oil prices are currently within a range that allows Saudi Arabia to break even on a broadly expansionary fiscal path and cover its import costs, the reform momentum that was initiated by the 2014 collapse in oil prices would be tested in the event of a similar decline in oil revenues. Generating hard-currency financial income is a critical function of many SWFs, with offshore allocations accounting for all or most assets of the Norwegian, Abu Dhabi, Kuwaiti, Qatari and Chilean funds (in addition to several non-commodity SWFs, such as those from New Zealand, Australia, China and Singapore). In this section, we outline the conceptual case for accumulating foreign assets, particularly in resource-dependent economies, before considering how such a policy could be designed and implemented in Saudi Arabia.

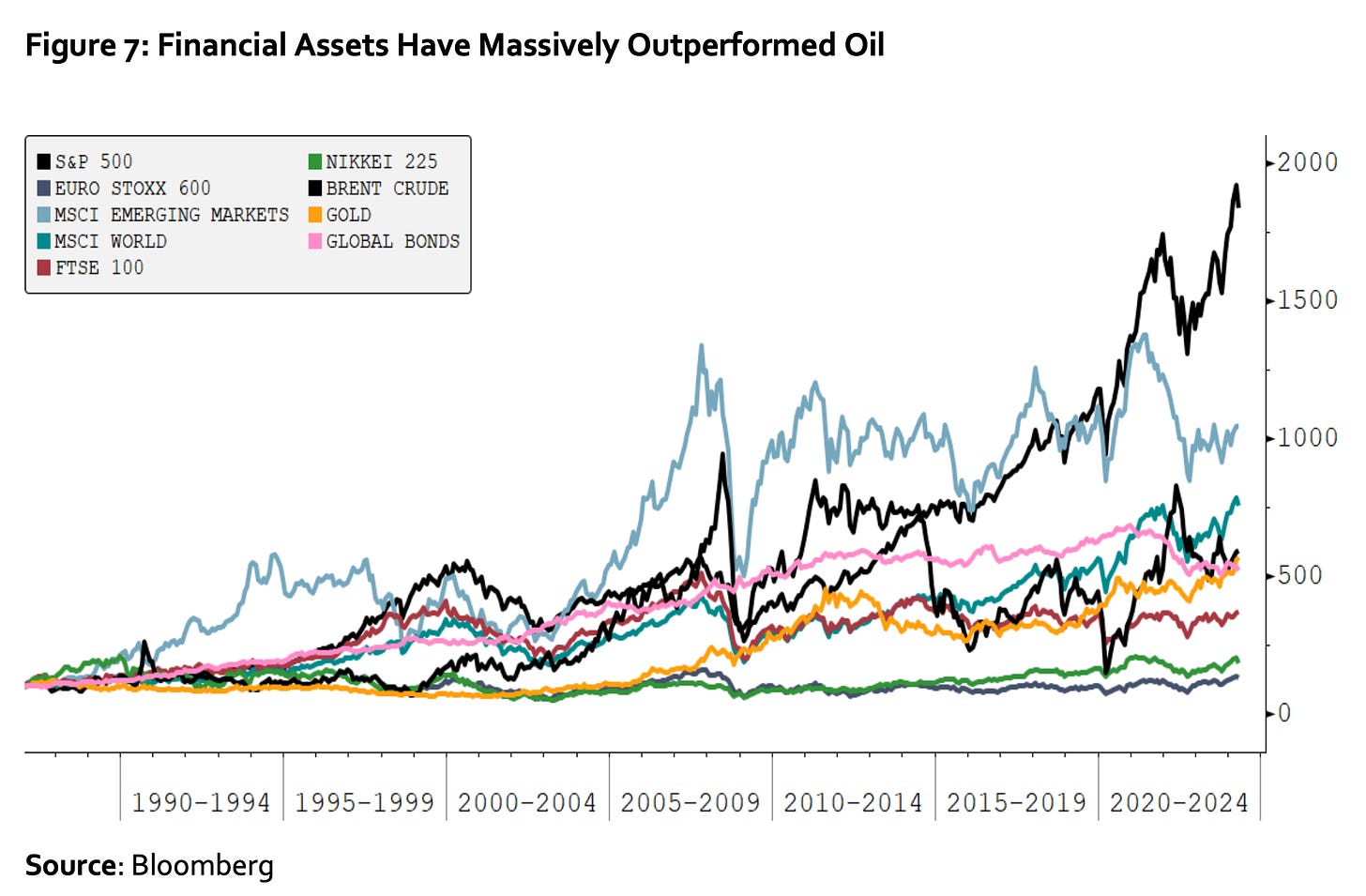

Oil dominates the Saudi sovereign balance sheet. If the value of undeveloped oil assets is included, the sovereign wealth of Saudi Arabia remains overwhelmingly concentrated in oil. From a diversification of wealth and long-term risk management perspective, it is prudent to pursue opportunities to convert oil wealth into financial and other forms wealth. Knut Kjaer, a former head of the Norwegian SWF described the fund as “an instrument for diversifying government wealth and transforming income from temporary petroleum resources into a permanent flow of investment income” (Kjaer, 2006). He further pointed out that oil-price volatility has historically been far larger than the variations in the return on equities and fixed- income instruments: “The risk is (historically) more than twice as high as that associated with a well-diversified portfolio of international equities” (Kjaer, 2006).

The historical excess volatility of oil over financial assets has not resulted in higher return. Indeed, even without accounting for higher volatility, the long-term return on oil has been poor relative to financial assets, particularly equities (see Figure 7). Based on historical patterns, then, the case for converting oil wealth into financial wealth at the highest rate possible is compelling from both a risk diversification and return perspective.

Related to the logic of wealth transformation from oil to financial assets are the benefits of diversified income. Earlier, we noted that Saudi Arabia has made progress toward generating non-oil revenues and issuing foreign debt, which provides some insurance against risks to oil revenues. However, future non-oil revenues and the cost of borrowing are likely to be correlated to oil revenues, underlining the case for diversifying revenue.

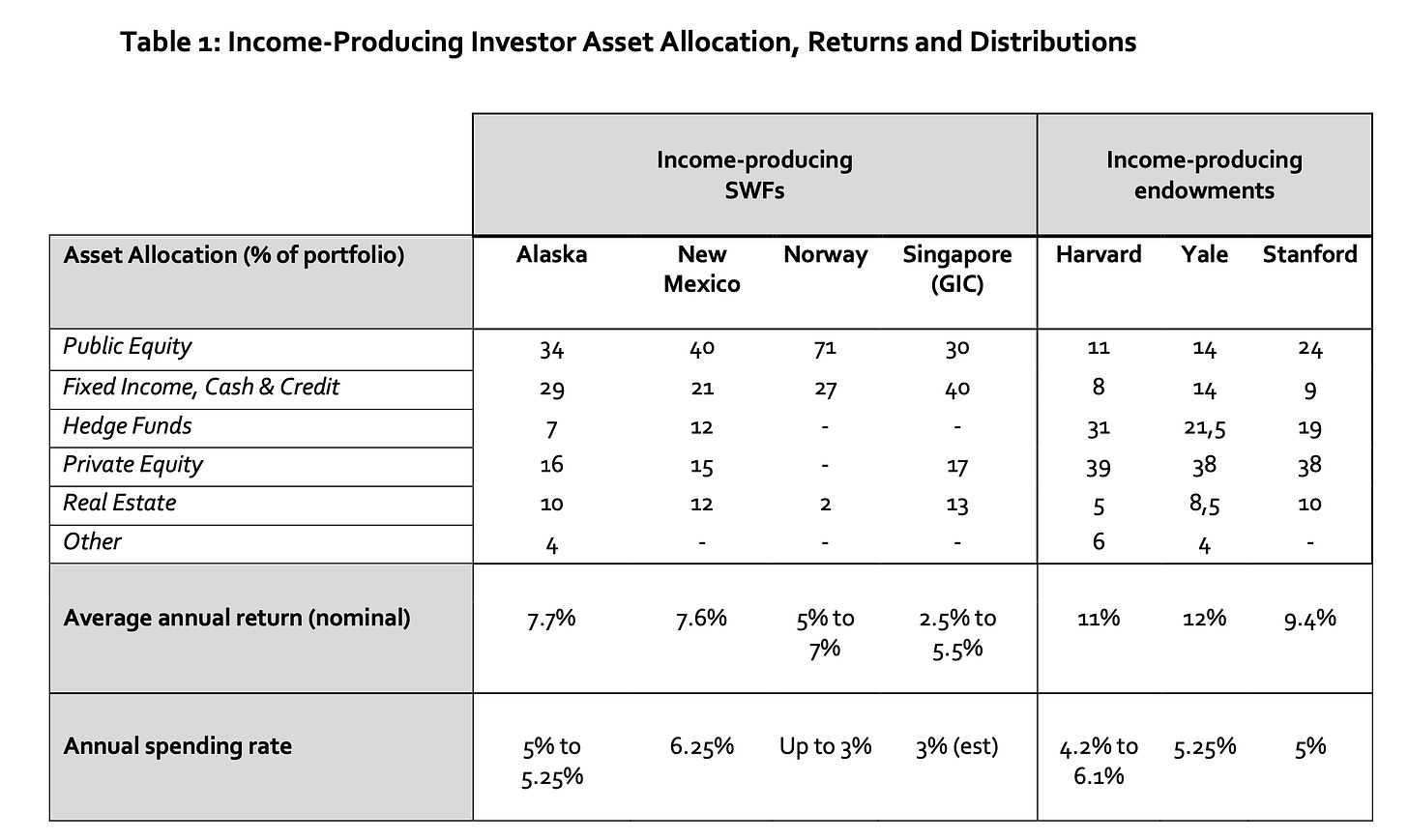

Distributions based on income and returns from a portfolio of financial assets can fulfill exactly this purpose. Indeed, income provision is a critical function of several prominent SWFs – notably the Kuwait Investment Authority, the Government Investment Corporation of Singapore, and the Alaskan, New Mexican and Wyoming permanent funds – as well as the famous endowments of leading universities, most famously Harvard, Yale and Stanford (see Table 1).

One added benefit – which does not apply to US permanent funds and university endowments – that many commodity-exporting countries enjoy from holding foreign assets in their SWFs is that it provides access to foreign-exchange income, even when oil- and other commodity- revenues decline (either cyclically or structurally). This promotes exchange-rate stability and helps pay for imports, without having to resort to ad hoc drawdowns on foreign exchange reserves and other buffers.

Another reason for holding a share of oil revenues in the form of financial assets, and particularly foreign assets, is that domestic investments are typically subject to diminishing returns to scale, particularly over the short to medium term. There is a large literature surveying a decline in quality and efficiency when public investment is ramped up over the short term, particularly in the context of various capacity and import constraints.

In short, this literature finds that there are thresholds in both the size and pace with which public investment projects can scale, without adverse outcomes across a broad range of measures. These measures include cost escalations, time overruns, the quality and durability of infrastructure, and economic and social efficiency. Warner (2014) and Flyvbjerg (2014) find that megaprojects and large investment booms typically end with higher public debt burdens and limited long-run growth dividends. Evidence based on project-level data supports the conclusion that outcomes worsen in periods of rapid public investment scale up (Presbitero, 2016).

In economies that lack flexible labor markets, local know how and intermediate inputs (such as energy sources, raw materials, semi-finished goods, and capital equipment - or the physical infrastructure required to import and efficiently distribute them at scale), “absorptive capacity” for large increases in capital commitments may be limited. This threshold effects, and the closely related “Dutch disease”, has often led countries to adopt policies of investing a significant share of their commodity windfalls outside of the domestic economy – either for savings exclusively, or a combination of savings and income generation. In this context, it is encouraging and appropriate that the PIF, alongside Vision 2030 architects, have recently spoken about the need to carefully reassess major investment timelines and costs, while prioritizing the most urgent and impactful projects first. Indeed, this argument speaks directly to our expectation that the current Big Push will inevitably – and productively – evolve into a Long Push, extending well beyond Vision 2030’s targets for the end of the current decade.

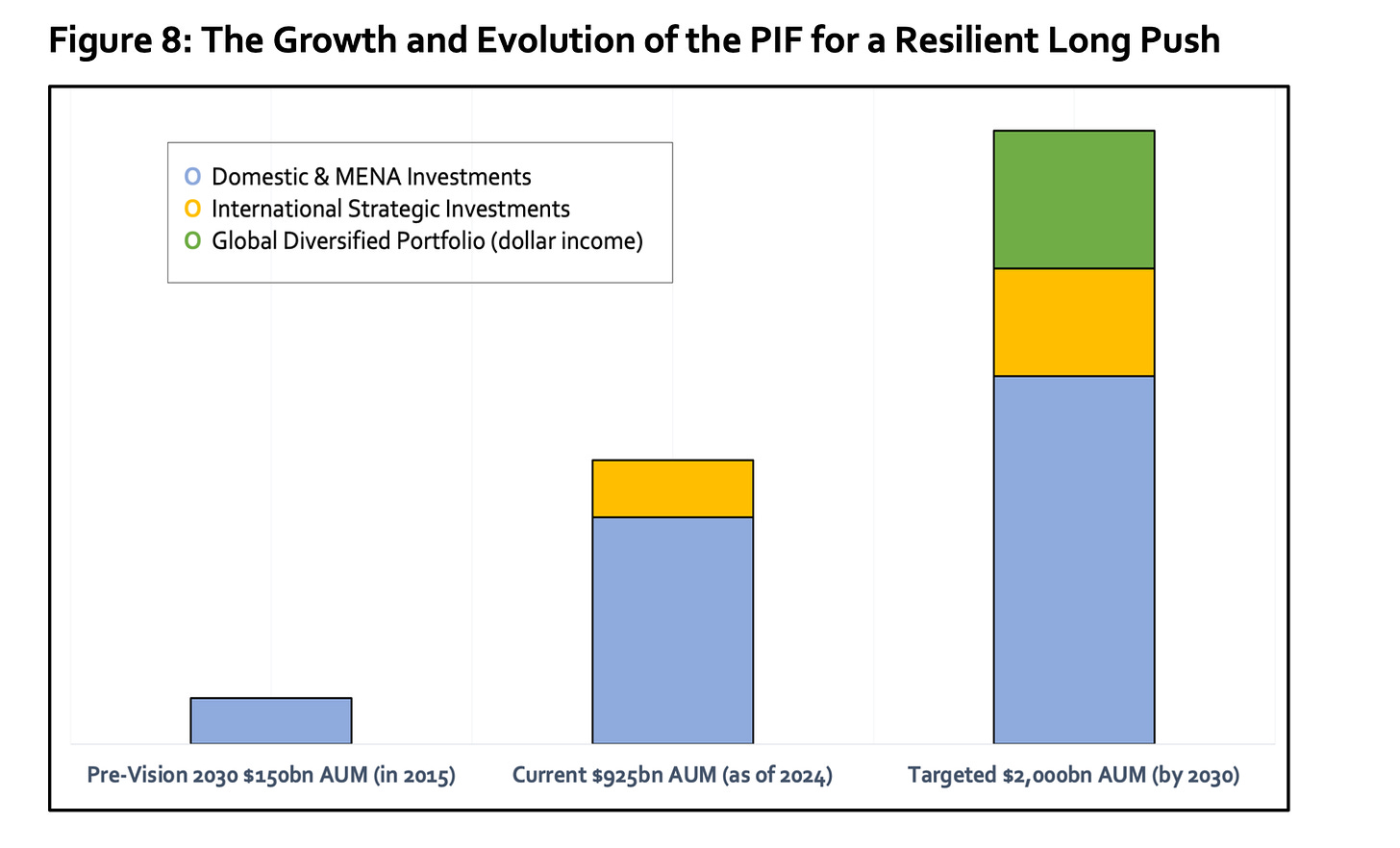

Over the medium- to long term, rule-based fiscal policy and a strategy aimed at increasing foreign assets and the income generated on them can increase the resilience of Saudi Arabia’s Long Push for diversification. Beyond 2030, the growth of an income-generating foreign-asset portfolio would fit with a natural evolution of the PIF as a mature SWF – in line with the Vision 2030 target that anticipates its total assets to grow to US$2 trillion by the end of the decade (see Figure 8). We do not recommend that the PIF distributes regular investment income and returns to the budget at this stage of its evolution – however, this can be regarded as a medium- to long- term objective, subject to further research. Beyond 2030, the PIF will likely reach the size and maturity – and potentially receive a greater share of annual oil revenues – to allow it to fulfill this income-provision function to the Saudi budget. Note that many global SWFs that currently provide regular fiscal income only assumed this function after several years in an “asset- accumulation phase” during which they built their credibility, legitimacy and ultimately positioned to their portfolios to balance income and long-term growth.

The PIF has already significantly broadened its portfolio over the past decade t0 include international (and MENA-region) investments alongside its transformative domestic investments. Our proposals would allow for the total amount of committed capital in domestic/MENA and international-strategic investments to continue growing, while also adding the critical layer of income-generating investments in diversified global assets over the coming decade. If there is a significant positive shock to oil revenues, consideration should be given to further raising the PIF’s ownership share in Saudi Aramco. This would enable the PIF to direct a larger portion of its inflows to investments in foreign income-generating assets without compromising its continued scaling up of domestic investments. In the following section, we demonstrate how rule-based fiscal policy can stabilize public spending and establish a framework for the rebuilding and eventual sustainable use of Saudi Arabia’s foreign assets.

To read this paper in full, click here to visit its SSRN Page.